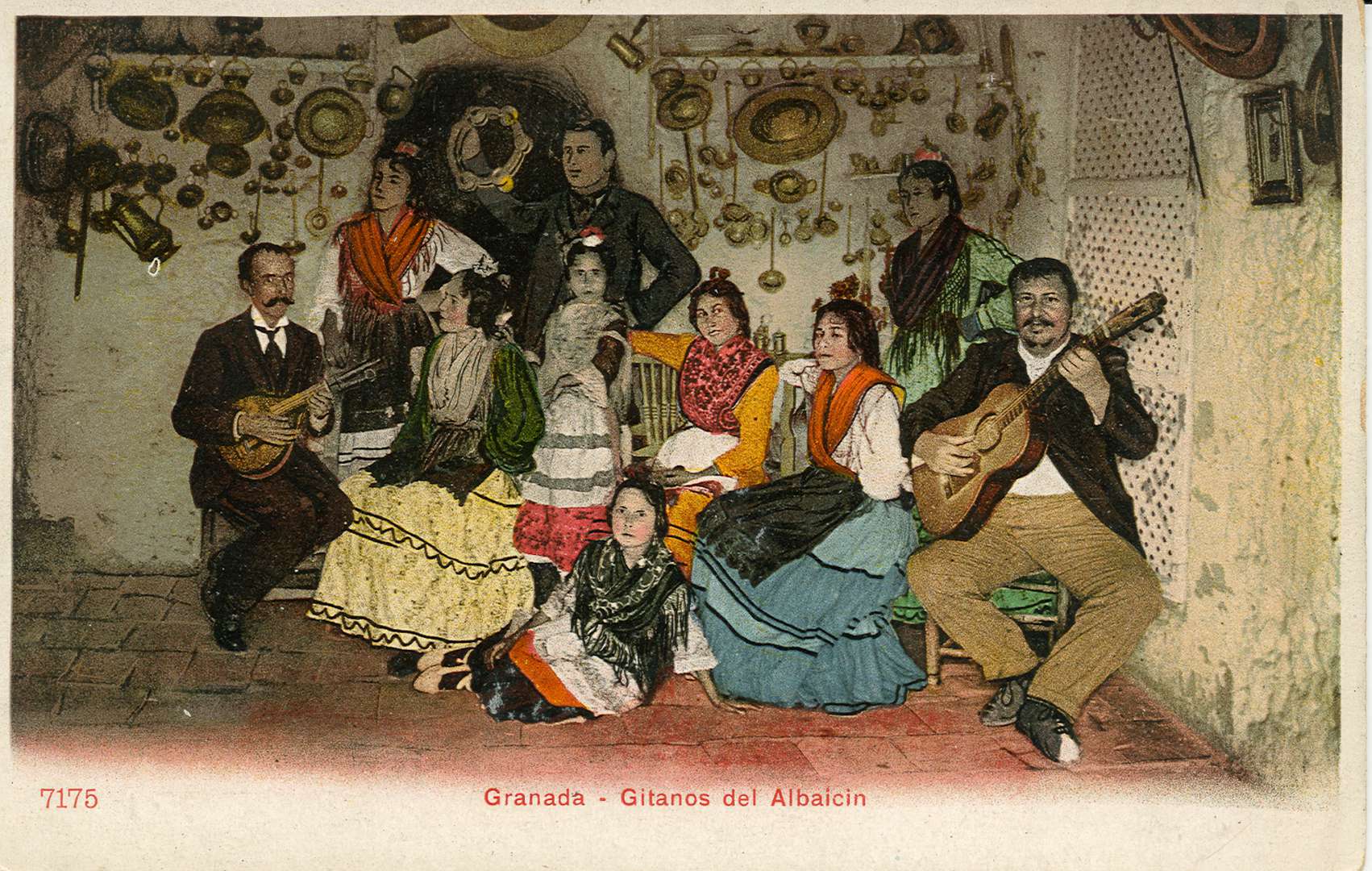

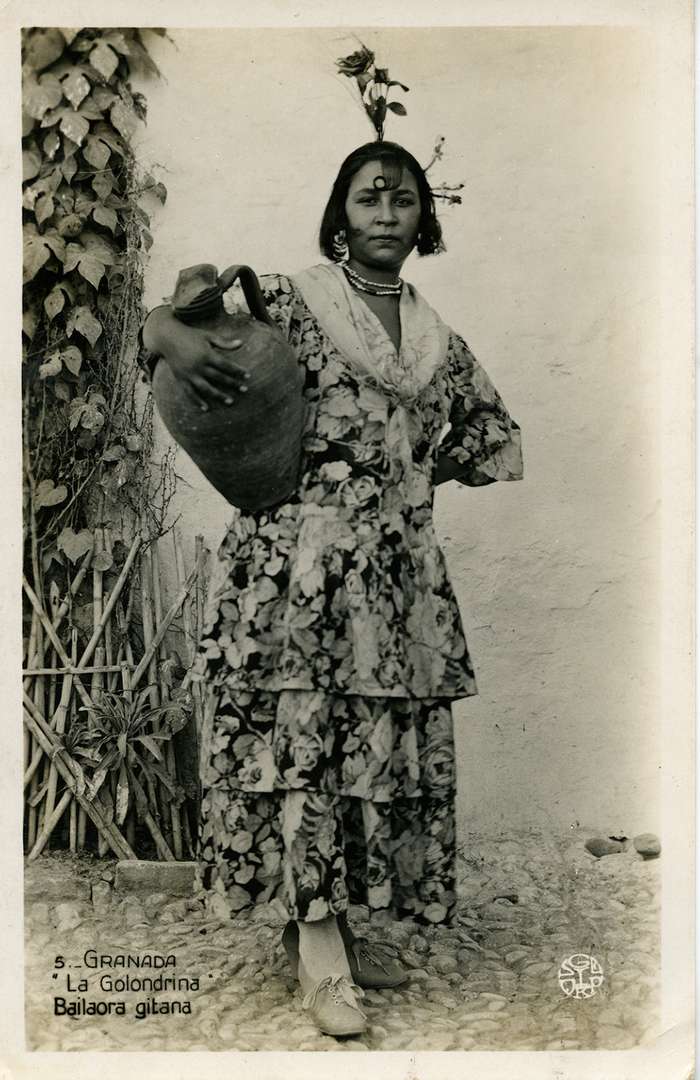

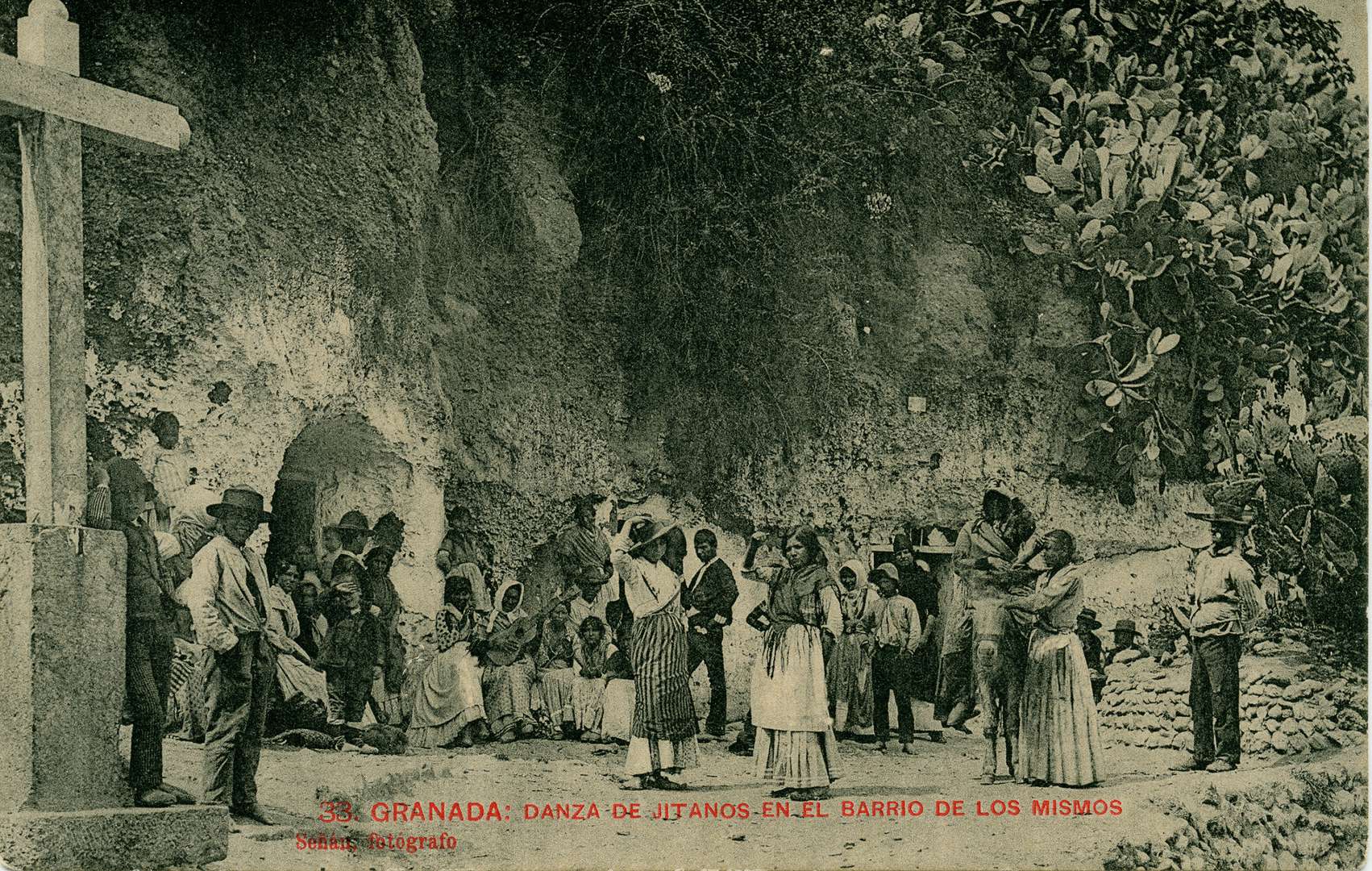

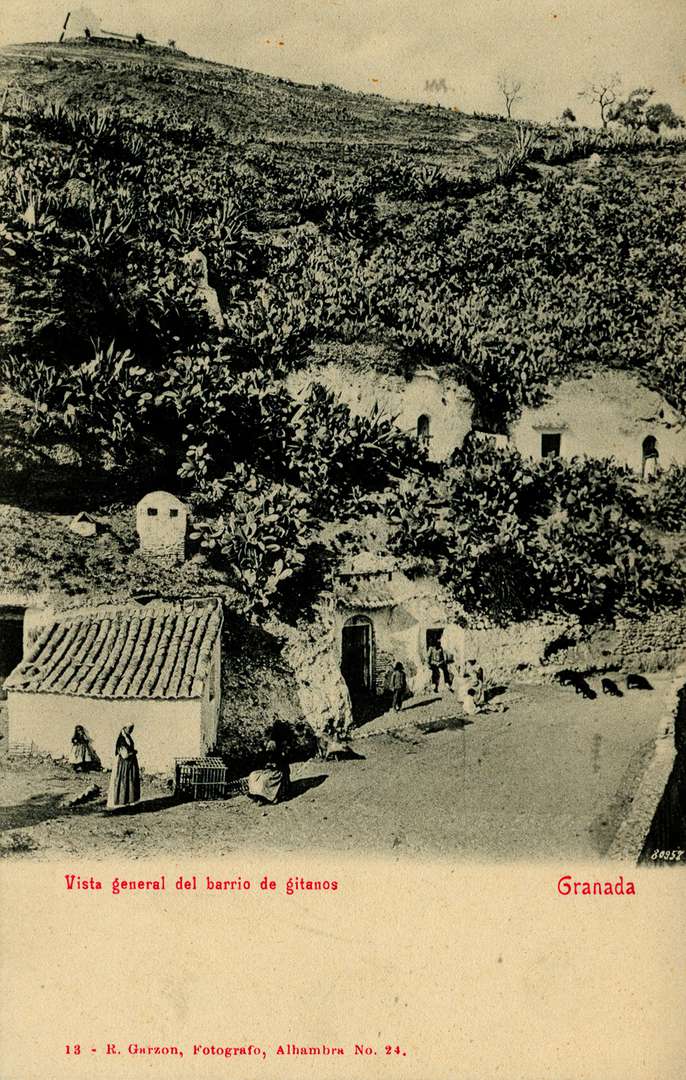

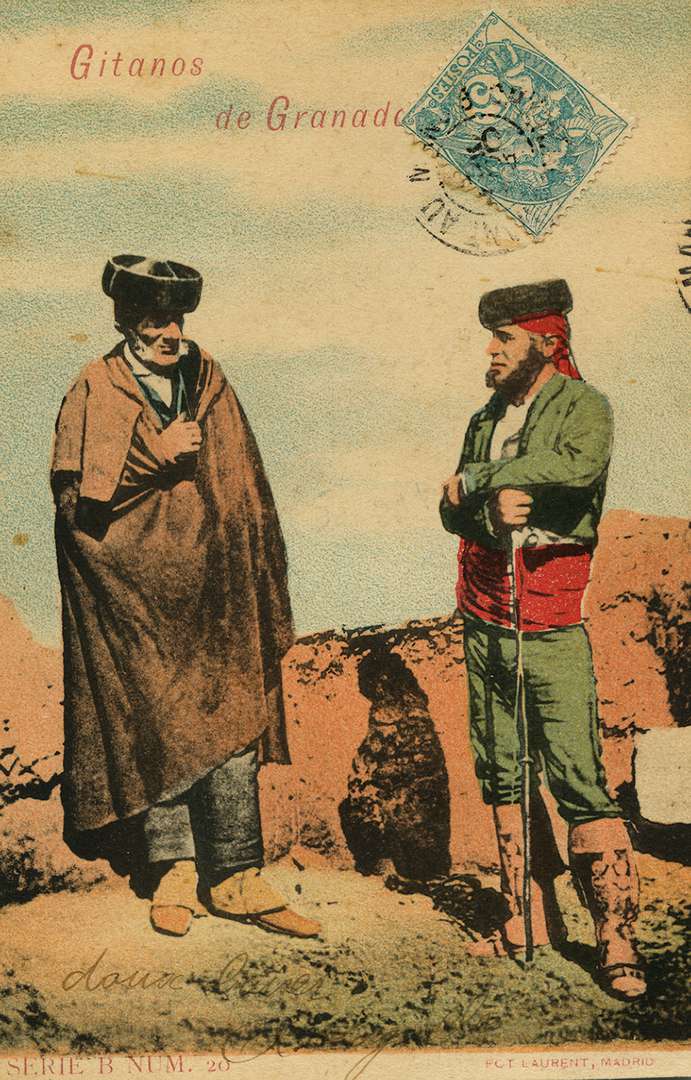

Flamenco came into being in Andalusia, Spain: from the mixture of its cultures and the genius of its creators were born forms that were unique in the world. The western Andalusia region gives us the ‘triangle’ of Seville, Jerez de la Frontera and Cádiz, whose importance is undeniable thanks to its contribution of a melting pot of Roma songs including those in the soleá and siguiriya styles. Nevertheless, history has often overlooked the fact that on the other side of the map of Andalusia there is an area which has been profoundly influenced by flamenco: Granada. It is a first-class setting for flamenco which has generated a rich variety of flamenco and Gitano songs and played a pioneering role in understanding flamenco as a professional art form.

The second half of the nineteenth century saw the development of many cantes [songs] that were practiced within families. This was a period when the various palos [forms], rhythms, instrumentation, ways of delivery, structures and cadences were transformed, formed and consolidated – a process that still continues to this day.

It was around then that Silverio Franconetti became an outstanding artist, producer and businessman who gave flamenco the opportunity of becoming professionalised and opened up the music for the public at large.