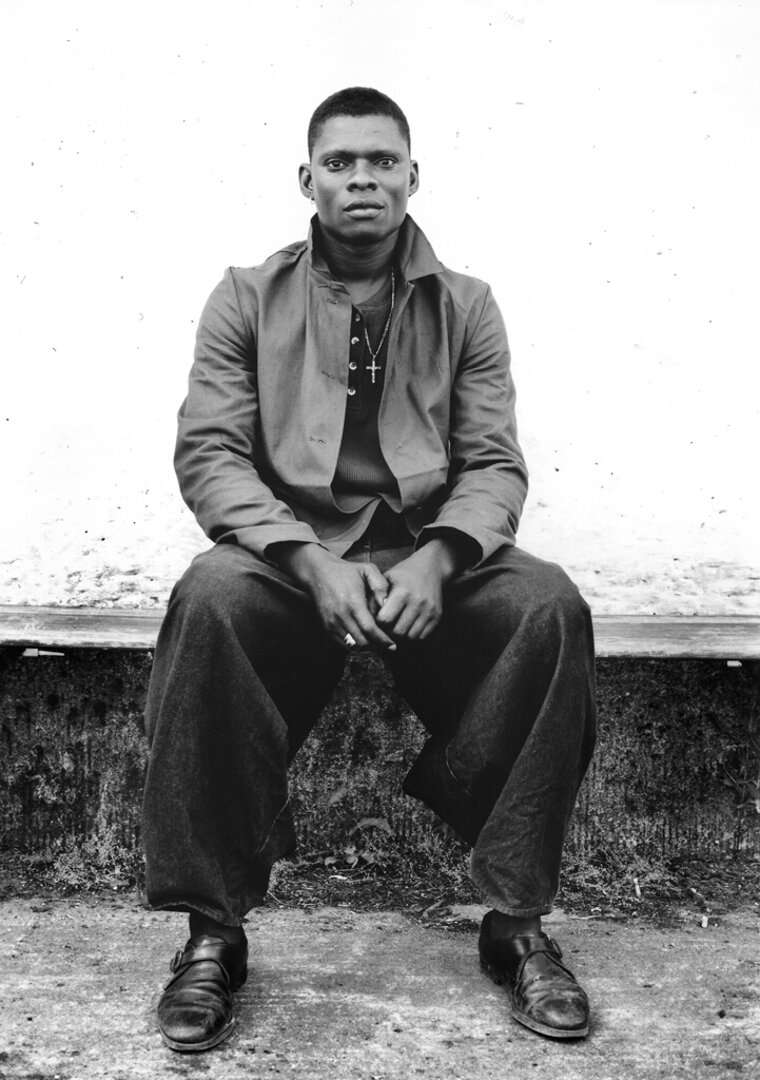

A few decades after its invention in 1850, the metaphor of “the paintbrush of nature” turned photography into an instrument and “a symbol of scientific objectivity which was supposedly able to prevail over every form of human caprice. Belief in this form of objectivity characterized every area of science” (Bredekamp 2004, 18). Photography was thought to enable the production of objective visual representations, as its mechanics resemble that of the human eye. Contemporary arguments considered representations of the “Other” (non-white, non-European people) to accurately portray their “level of development” (particularly as compared to the Western world), without taking the constructedness of representation into consideration. The camera as a technical and thus neutral eye virtually embodied the Enlightenment ideal of objectivity.

The period in which photography emerged was shaped by scientific positivism, based on a belief in empirical truth accessible through visual evidence. As machines were considered more reliable than humans, the photographic process was seen as a more accurate scientific tool with which to represent reality. To perceive a photo as an unmediated copy of the real world is based on the myth of photographic truth (Sturken and Cartwright 2001, 16). Saturated with these discourses, photography and the photographic gaze – as a scientific, objective methodology and mode of reasoning believed to enable access to truth and reality – played a part in establishing power relations.