From the 1960s onwards, Romani writers began to depict their culture in Finland. The topics varied from culture-specific resonances to the problems of contemporary Romani youth. Although Roma have resided in Finland since the sixteenth century, they were not officially recognised as a national minority until 1995. Therefore, the questions of national rights and citizenship are recurrent themes in Romani literature.

Books of Birds: Romani Literature in Finland

Veijo Baltzar (b. 1942) is a pioneer of Romani literature in Finland and internationally. His works cover a wide range of literary genres, and he has published novels, poems, librettos and plays. In his early publications in the 1960s, Baltzar skilfully depicted the travelling lifestyle and Romani customs such as the blood feud in Verikihlat [Engagement of Blood), 1969.

Baltzar’s novel Polttava tie [Burning Road], 1968, depicts the contribution of Romani soldiers in the fighting between Finland and the Soviet Union in World War II and emphasises this as a sign of citizenship. In the novel, an old Romani man describes how his family were confronted with racism on the home front while he was fighting for all Finnish people in the war.

Musta tango [Black Tango], 1990, depicts the drifting lifestyle of Romani youth in an urban setting. The protagonist, Elias, who grew up in a children’s home, is an outsider both in the Romani community and within the dominant culture. Here, the question of an authentic Romani identity is explored by characters whose position is in between the dominant and minority culture. (Kopsa-Schön 2002).

Veijo Baltzar (born 1942) is a forerunner of Romani literature in both Finland and worldwide. He was born in Suonenjoki in central-southern …

Baltzar’s novels are written in a realistic style, although they contain melodramatic and poetical elements. They also show a profound knowledge of folklore as, for example, in »Käärmeenkäräjäkivi« (1988, excerpts translated into English as »The Snake Trial Stone«, a mystery of a stolen stone, which deals with personal and collective ethics.

In the 2000s, the author moved from the stories of individual Romani characters to an epic depiction of Romani mythologies and silenced histories. In Phuro (2000), the place and date of the events are not named, highlighting the universality of the themes, one of which is the tension between traditional Romani values and materialist culture.

In his novel Sodassa ja rakkaudessa [In War and in Love], 2008, Baltzar pays homage to Romani victims of Nazi Germany. The protagonist is the pickpocket Kastalo, who has survived a concentration camp:

‘[...] One should hope that scholars will mention him [Kastalo] in their studies, side by side with the Jewish people.’

In his study Kokemuspohjainen filosofia 2012 [Towards Experiential Philosophy], 2014, Baltzar claims that the traces of the Holocaust can still be detected in the treatment of minorities in Europe.

Armas K. Baltzar explores social exclusion in his novels Sadeaika [Rainy Season], 2007, and Katuhaukat [Street Hawks], 2009, yet Romani identity is not always foregrounded in his works. Sadeaika, for example, deals with love between disabled people, a subject seldom addressed in Finnish fiction.

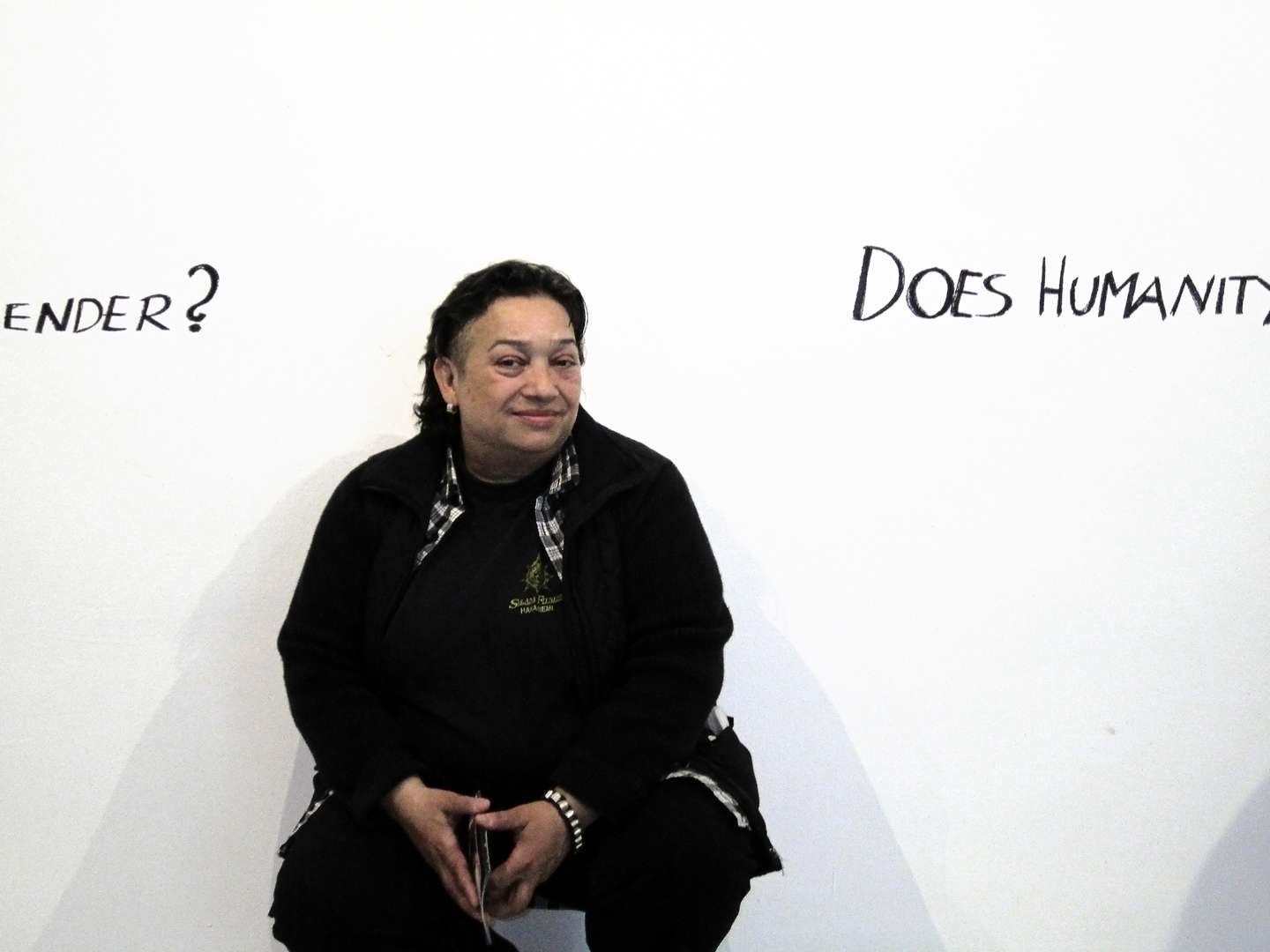

Kiba Lumberg (Kirsti Leila Annikki Lumberg) is one of the most visible and versatile Romani artists and activists in Finland. Lumberg was born …

Kiba Lumberg (b. 1956) had her debut as a novelist in the 2000s with her trilogy Musta perhonen [Black Butterfly], 2004, Repaleiset siivet [Tattered Wings], 2006, and Samettiyö [Velvet Night], 2008. The trilogy (published in a single volume in 2011) presents the life of a poor Romani family in East Finland in the 1960s and 1970s from the viewpoint of a little girl, Memesa.

The trilogy is a novel of development and a portrait of the artist. Memesa, at the start of her career as an artist, demonstrates the oppression of women at the Venice Biennale by showing a Romani woman’s traditional dress pierced with knives. This can be read as a fictionalised account of Kiba Lumberg’s own participation in the Venice biennale in 2007. Her depiction of violence in the novels as well as in her art work was criticised by Romani readers. Although the trilogy questions the heterosexual power structure that ‘oppresses human rights all over the world’, most critics, however, ignored the role played by Memesa’s lesbian identity (Lappalainen 2012; Gröndahl 2010). The dream sections of the novels introduce elements of fantasy into the realistic mode of the trilogy.

(Auto-)Biographies

In his biography of the musician Henry (Remu) Aaltonen (b. 1948), entitled simply Remu (2016), Markku Salo makes extensive use of Remu Aaltonen’s distinctly personal language, which became known as ‘Remu language’ after him. The biography tells the reader about Aaltonen’s poverty-stricken childhood in Espoo, where his family lived in a railway car. Later, it recounts his successful career as the ‘king of Finnish rock ‘n’ roll’.

Armas Lind's (1928–2017) autobiographical account Caleb – romanipojan evakkotaipale [Caleb – a Refugee Journey of a Romani Boy], 2004, belongs to refugee literature as well as to Finnish and Swedish-Finnish literature. It is a touching portrayal of the hunger and cruel treatment of a Romani child in Sortavala, which used to be the ‘capital’ of Finnish Roma in the 1930s and 1940s.

Caleb is a historic document of Romani culture in the Karelia region between present-day Finland and Russia, which has hardly been explored. After the wars between Finland and the Soviet Union (1939–1944), the Karelian Romani community lost all their former networks and livelihoods, such as farriery.

Riikka Tanner’s and Tuula Lind’s Käheä-ääninen tyttö. Kaalengo tsaj [A Husky-voiced Girl], 2009, documents the apartheid-like treatment of Roma in the 1950s and 1960s. Lind’s life story recounts her traumatic experiences in a children’s home. It turns to confessional mode when Lind recounts her life as a thief and drug abuser who finally ends up in prison. Later, she describes emerging Romani political consciousness in the 1960s and 1970s.

Miehen tie [A Man’s Way], 2008, by Rainer Friman (b. 1958) combines sharp cultural and social criticism with self-scrutiny. The text discusses the problems of Romani youth and criticises the romanticisation of Romani culture.

Children’s books

Veijo Baltzar’s book of fairy-tales Mustan Saaran kristallipallo [The Crystal Ball of Black Saara], 1978, tells the story of a search for virtues such as wisdom, empathy, equality and forgiveness. Inga Angersaari’s Romaniukin satureppu [Fairy-Tale Bag of Romaniuk], 2001, describes how cultural memory is passed on to the next generation. Rassako reevos. Yökettu [Night Fox], 2017, by Helena Blomerus, Satu Blomerus and Helena Korpela, is written in a realistic, dialogue-like mode, with many voices speaking. It narrates the daily life of the Romani girl Mira and her family, who lives in harmony with the members of the dominant culture (Sinko 2010), suggesting that Finnish society had become culturally more diverse by the 2010s.

Conclusion

Romani writers in Finland depict striking poverty, describing how Roma fall through society’s safety nets and their strategies for survival. Romani identity is presented as both a continuation of traditions and a product of changing lifestyles (Gröndahl & Rantonen 2013). Many writers deal with the traumatic experiences of Romani children in children’s homes during the 1950s and 1960s. The shared history of Roma is powerfully presented in Finland’s Romani literature and also includes invaluable documentation of the silenced histories of the Holocaust and the experiences of refugees.

Rights held by: Eila Rantonen (text) | Licensed by: Eila Rantonen | Licensed under: CC-BY-NC 3.0 Germany | Provided by: RomArchive