‘Throughout history from the Roma’s arrival in Europe to their extermination under the National Socialists – the “great narrative” about a primitive people in the midst of civilisation was written without the Roma groups themselves.’1

Klaus Michael Bogdal

Towards a New Art History The Image of the Roma in Western Art

As a result of the modern discipline of visual studies, it is now considered a banality that the visual should be conceived as a language. The idea of the ‘opaque’ developed by cultural theorist J. T. Mitchell is productive in this sense, as it stipulates that

‘instead of providing a transparent window on the world, images are now regarded as the sort of sign that presents a deceptive appearance of naturalness and transparency concealing an opaque, distorting, arbitrary mechanism of representation, a process of ideological mystification.’2

This essay attempts to reflect on the opaque veil covering the depictions and representations of Roma in ‘Western art’.3

From the fourteenth century onward, Roma served to influence the iconography of European art, which, in turn, through the various products of visual culture became one of the most important instruments in colonising Europe’s largest minority.

It would be impossible to identify all the representations of Roma throughout art history, and yet it is an important and urgent task for the European Roma movement. ‘The Image of The Black in Western Art’,4 for example, is a comprehensive research project into Black representation and participation in art history. The Du Bois Institute was established in 1975: the project was ‘reinvigorated through the collaboration of Harvard University Press and the W. E. B. Du Bois Research Institute at the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research to present new editions of the coveted five original books, as well as an additional five volumes’ in 2010,5 I believe the publications and the related website identifies several ethnic minorities as black in representations of the ‘other’, and research into the image of Roma must now engage in a strange postcolonial power game, just as it must reclaim certain representations.

This essay makes no claim to exhaustiveness, and as such concentrates firstly on artworks that were key to the development of iconographic models, and secondly, with regard to the narrative, on studies in art history that defined the academic discourse and/or shaped its turns.

Starting from the first, fifteenth-century images of Roma, the essay analyses the iconographic models that became established in visual culture from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century, and were repeated like a pattern; this is followed by a look at the idealising exoticism of Romanticism, the modernist image of Roma and their representation in the twentieth century.

My studies and observations in pre-modern art owe their legitimacy to Erwin Pokorny, an acknowledged expert of Flemish painting at the University of Vienna, and to Alena Volrabova, a museologist in the fifteenth-century graphic art department of the National Gallery in Prague.

Erwin Pokorny delivered a lecture on the subject at the 32nd conference of CIHA, whose theme was ‘Crossing Cultures: Conflict, Migration and Convergence’; he also acted as my mentor for the first part of the dissertation.

Collecting what seems like an endless number of images of Roma has become necessary firstly so that their examination is possible, secondly so that their deconstruction, an objective of Roma art, can take on a function, and thirdly, so that we can better understand how analysing visual products furthers the expansion of knowledge about Roma and their history.

Walter Mignolo claims that we can only understand the logic of social inclusion if we go back in time to the colonial history of Europe, to the slaveholding and colonising practice of the continent, which served the capitalist growth of white Europeans. Needless to say, its mechanisms continue to define human relationships to this day. For centuries, European knowledge production – books, educational systems, encyclopaedias and works of art – made the history of colonialism the norm. The visual products discussed here were conducive to the emergence of today’s visual hierarchy and are now its essential components, defining even the collective memory of the Roma themselves.

We must first understand what the knowledge is that acts as a power system so as to unlearn it.

The Romani artists considered in subsequent essays make attempts to dismantle these images and the hierarchic relationships that have emerged by their agency – to decolonise art and life. To be able to describe this paradigm shift later on, or to assess the results of this endeavour, it is essential that we be familiar with the basic position from which Romani intellectuals and artists are speaking. To echo Walter Mignolo, we must first understand what the knowledge is that acts as a power system (and from which the Roma de-link themselves) so as to unlearn it.

It has become widely established that Roma migrated from India to Persia in the early Middle Ages, settling in Byzantine territories, whence they moved on sporadically in smaller groups. One such movement occurred when the bubonic plague reached western Anatolia around 1347 and set off a major wave of migration towards Europe. In all likelihood, this involved some Roma, especially given that they were blamed for the epidemic.6 (The Indian origins and migration of Roma were only demonstrated in 1763 by István Vályi, a Hungarian-born student of theology at Leyden University.)

See also: Migration and the Roma

By the thirteenth century, Roma had arrived in the Balkans, and from the early fifteenth century onward they were living all over Europe. They are first mentioned in writing as far back as 1399, when a Romani groom is mentioned in the Book of Executions of the Lord of Ruzomberok.7

In the decades that followed, Roma moved northwards and were reported in Hildesheim in 1407, Basel in 1414, Zurich in 1417, Antwerp in 1419, Bologna in 1422 and Paris in 1427. The arrival of the Roma in Western Europe in the early fifteenth century coincided with the Northern Renaissance in art. The first depiction of a Romani is a German drawing from the last quarter of the fifteenth century, now archived at the National Gallery in Prague. It shows a mother holding her child, accompanied by the inscription ‘Ziginer’ over her head.

She is wearing a turban and a long cloak, held together by a knot on one shoulder. A witness account from August 1427 confirms that her clothes are typical of Roma women of the time. The description which details the arrival of a group of 132 Roma in Paris was published in the Journal d’un bourgeois de Paris.8

'Most of them [...] had their ears pierced and wore a silver ring [...] or two [...] in each. The men were very dark, with curly hair; the women were the ugliest you ever saw and the darkest [...]. They had no dresses but an old coarse piece of blanket tied on the shoulder [...]. In short, they were the poorest creatures that anyone had ever seen come into France.’9

Journal d’un bourgeois de Paris

This French source refers to the alien group as ‘bohemiens’ because they had been assured safe conduct by the king of Bohemia. Owing to their oriental and exotic look, they were as likely to be called Saracens, the word commonly used to refer to Muslims during the Middle Ages. Since the newly arrived Roma claimed to have come from ‘Little Egypt’, Roma ended up being called Egyptien in French-speaking territories, and Egyptener or heyden (heathens) in the Netherlands. The words used today – ‘Gypsy’, ‘Gitano’,’ Gitane’ – all derive from ‘Egyptian’, although Little Egypt was in fact a region in the Peleponnese under Venetian rule, where Roma had settled for a time before continuing their way towards the interior of Europe, probably under pressure from Ottoman incursions. Note that the most common European terms, such as Zigeuner, Cingaro and Tzigan, derive from the Greek atsinganoi / athinganoi, which means ‘untouchable’.

According to the professional – and later technical – analysis of Alena Volrabova, the inscription ‘Ziginer’ is coeval with the drawing itself, making the latter truly the first representation per se of Roma people. The long cloak tied at the shoulder can be found in a number of other images depicting the ‘heathens’ of the Bible and Roma, though with an added characteristic not mentioned in the French source cited, namely Oriental striping. Similar striped cloaks can be seen in the tapestries of Tournai from the fifteenth century; in the woodcuts of Sebastianus Münster’s 1550 Cosmographia Universalis, which has a chapter entitled ‘Züginer’; and in another French representation, Recueil de la diversité des habits [On the Diversity of Clothes] by the Parisian François Desprez, dating from 1567.

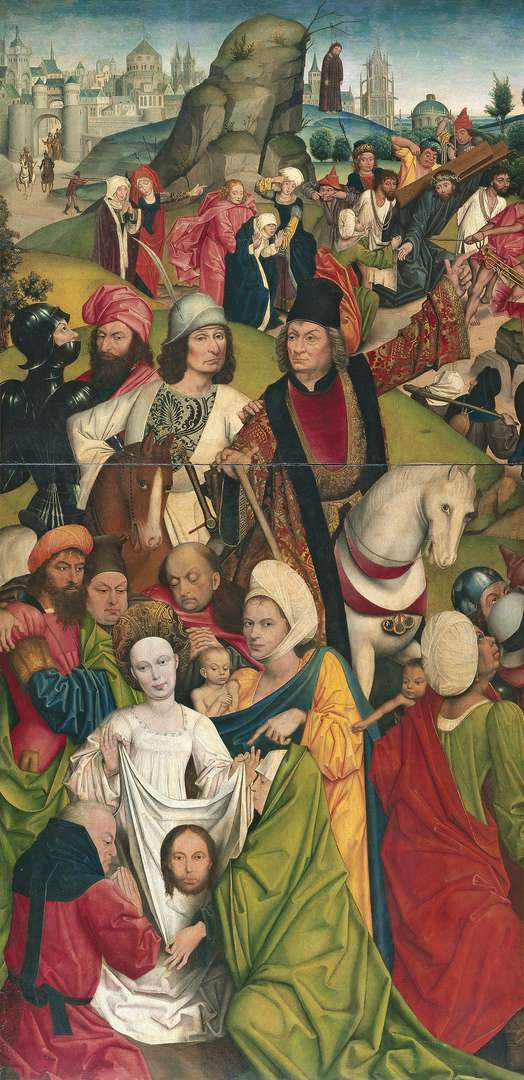

Different versions of the striped cloak or dress would continue to appear in artworks until the nineteenth century. In early (fifteenth-century) representations, Roma women almost always wear turbans, which are flatter than those in images of Muslim men. Muslim women did not wear turbans, and this flatter variety was distinctive of Roma, especially among women. Charles D. Cuttler, an art historian and acknowledged expert on the Northern Renaissance, was the first to identify this kind of flat turban in art history, worn by the figure of Mary Magdalene in The Entombment Triptych by the Master of Flémalle.

In his study ‘Exotics in 15th Century Netherlandish Art: Comments on Oriental and Gypsy Costume’, Cuttler points out the striking similarity between the travelling ‘Egyptians’ and this earliest European representation of the flat turban (and building on the idea, Erwin Pokorny would subsequently take an even closer look at turbans). On the left, Joseph of Arimathea wears a red striped cloak, and the body of Christ rests on a shroud with a striped edge. On the right-hand panel, the guard in the foreground wears a striped cloak, while the one on the left, who raises his hands in shock, wears a flat turban. There are a great many exotic elements in this early work of a new tenor in Flemish art, by an artist known for innovative and experimental solutions.

The Master of Flémalle’s Entombment Triptych is dated to 1420, a time when there were reports of a group of Roma travellers appearing in Brussels, led by a duke called Andrew.10 In 1421, another Roma leader, Michael of Latingham, visited Mons, the capital of Hainaut, as well as the nearby Tournai.11 The latter was the hometown of Robert Campin, who was presumably the Master of Flémalle. In all likelihood, the Master did not mean to represent Mary Magdalene as an ‘Egyptian’ but rather as a heathen, in the same way that he, or another artist associated with him, painted the Thracian queen Tomyris in a striped, flat turban.12 Erwin Pokorny also points out that in van Eyck’s Ghent Altarpiece from c. 1425–35 the Eritrean Sibyl is represented in a similar turban, as is a female figure in Jacques Daret’s The Nativity dating from c. 1434–35 (Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid). It is thus safe to conclude that the so-called travelling ‘Egyptians’ (i.e. Roma) were a source of inspiration for the greatest Netherlandish artists.

Cuttler also makes note of the fact that certain artists who illustrated the story of finding Moses modelled the Pharaoh’s daughter and her servants on the appearance of their own contemporary ‘Egyptians’. The Pharaoh’s daughter and her servants are half-naked in the scene, but wear large turbans to ensure they are accurately identified as ‘Egyptians’.

There are also several representations in which Jews appear in Roma clothes. The Bible provides many such examples, especially in the images of the Exodus. Take for instance the Gathering of the Manna scene in the Altarpiece of the Holy Sacrament by Dieric Bouts in Leuven, in which the Jewish women are clad in typically Roma clothes, and a child on the left is wearing an earring like the one mentioned in the French eyewitness account.

Ever since art historians began to study Roma clothing, approximately thirty years ago, a number of representations of women formerly thought to be Oriental have been reclassified as Roma.

One such example is the drypoint print by the Master of the Housebook, which J. P. Filedt Kok identified as the representation of a Roma in 1985.13

Dürer’s print known as the Turkish Family is another case in point. In all probability, there are still a number of images in which the representation of Roma is yet to be recognised. Take for instance the pen and ink drawing now in Munich which was made by Schongauer or a talented imitator: as Pokorny already pointed out, the woman’s turban and the garment knotted on her shoulder suggest that she is a Roma, but the title is simply Oriental Woman with Turban.

The clothing of Roma men at the time is less distinctive, though they can be recognised as jugglers, beggars and mercenaries. In the pages of early chronicles that represent the Roma as waiting outside city gates, their groups appear armed and in military clothing, along with the members of their families, women and children.

These images seem to lend support to the hypothesis – promoted above all by Roma scholar Ian Hancock, head of the Romani Archives at the University of Texas – according to which the Roma emerged from a caste of warriors, and served to halt the progress of Islam in India.

Based on linguistic and historical evidence, Hancock believes the Roma are the descendants of the Rajputs, and left the north-eastern part of India sometime during the tenth and eleventh centuries, chiefly as a result of the invasion of Mahmud of Ghazni, the Ghaznavid ruler who led seventeen attacks against India. Fleeing the terror, the Roma first stopped in Iran before moving on towards Byzantine and Greek territories.

Images of armed Roma men wearing hats with pheasant feathers became frequent from the 1500s; this accessory was common with mercenaries and bandits. An early example is Hans Burgkmair’s drawing, now kept in Veste Coburg. The piece is reminiscent of one of Jacques Callot’s engravings (in the series called Les Bohemiens), which was made much later and presents well-armed Roma in hats with long feathers.

Finally, we should take note of the representations of Roma men wearing some sort of turban, scarf or other unusual headgear. These images are particularly difficult to distinguish from depictions of Saracens; it is probably the characteristic hair, sometimes very long, and often curly, that makes these men look more Roma than Muslim – not to mention that wearing long hair under the turban was more likely to originate from India than from Turkish or Arab regions. One of the earliest examples is Stephan Lochner’s panel, now at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt, which represents the martyrdom of St. Andrew, and which features a man wearing this exotic headgear, in addition to two women who can be identified as Roma on account of the characteristics mentioned above.

The detailed portrayal of the Roma also appears in an engraved reproduction by Wenzel von Olmutz, which suggests that Lochner’s composition owed its popularity precisely to these exotic figures. Several such drawings of men from Martin Schongauer’s studio have survived. There is a specific iconographic tradition that calls for the study of representations of heathens, and more particularly those of Roma: the depiction of the man who assists those who take Christ from the cross.

The figure has a dark complexion, black curly hair under a turban, and sometimes wears a striped cloak. He either climbs the ladder, stands on its last step removing the nails, or brings the ladder to the cross. The earliest known example is one part of a triptych at Frankfurt’s Städel Museum, probably by the Master of Flémalle (there is also a copy at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool). This means that besides good Christians, heathens also played a part in Calvary iconography.

Another case in point is the two women in typically Roma attire in Westphalian master Derick Baegert’s fragmentary Calvary Triptych: one of them points to Veronica’s veil, the ‘Vera Icon’, while the other looks straight at the viewer.

It is thus hardly surprising that the dark-skinned Roma came to signify morally questionable types in the iconography of Christianity.

Legends of the Roma’s connection to the crucifixion have survived in a number of different historical and ethnographic sources. According to sixteenth-century accounts, the Roma were given a nomadic lifestyle as punishment for not providing the Holy Family with refuge in Egypt.14 There are even written descriptions of the myth according to which the nails for the crucifixion were made by a Roma smith. German anthropologist Ines Köhler-Zülch highlights these early stories as part of her research into the criminalisation of Roma in Europe. In the Roma’s own version of the myth – handed down through tales, legends and songs – a Roma stole the fourth nail that was to pierce Jesus’ heart, which God acknowledged by allowing the Roma to steal without fear of damnation.15

In another version of the tale – which is analysed by British encyclopaedist Francis Hindes Groom in his 1899 volume, Gypsy Folk Tales16 – the fourth nail is stolen by a Jew, who is then christened and becomes the ancestor of the Roma.17 Considering the dark complexion of the women in the painting, it is reasonable to ask whether the painter sought to represent heathens or was familiar with these legends about Roma, in which case this image is a clear-cut representation of Roma.

Most often, however, Roma are represented as evil enemies of God. There are several sources that trace Roma back to the condemned or denied characters of the Bible. One such character is Adam’s son Cain, whom God condemned to a fugitive life. Another one is Ham, who was cursed by his father Noah and went on to become the forefather of the dark-skinned Ethiopians, Libyans, Egyptians and those who lived in pre-Hebrew Canaan. Another case in point is Ishmael, who was driven away by Abraham along with his mother, Hagar, and who became the forefather of the Arabs.

It is thus hardly surprising that the dark-skinned Roma came to signify morally questionable types in the iconography of Christianity. One of the most famous painters of the ‘diabolical’, Hieronymus Bosch, frequently includes beggars and disabled people in his pictures, adding bodily features that stir up associations with the devil. A similar antipathy informs his Roma figures, an early example of which can be observed in the malicious-looking soldier to the left of Christ in Ecce Homo, now in the Städel Museum in Frankfurt.18

His skin is grey, his brown hair is dishevelled, and he wears a flat turban and an earring. Similar figures appear as Jesus’ enemies in Bosch’s Christ Carrying the Cross, housed at the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent. One of them wears a scarf with a striped pattern, with two ring piercings in his jaw. Another such figure is presented frontally, also with two rings on his face. The rings are connected by a chain, which may well be more than just a figment of Bosch’s imagination. Similar rings and jewellery can be seen in the aforementioned triptych by Derick Baegert, painted a few decades earlier.19 Baegert and Bosch must have heard about the jewellery-wearing Roma, and (ear and nose) rings connected by chains – which, incidentally, Rajasthan women continue to wear to this day.

Ruth Mellinkoff, art historian at the University of California, Berkeley, and author of Outcast: Signs of Otherness in Northern European Art of the Late Middle Ages (1994), suggests that the conscious distortion of facial features led to the need to use specific attributes if an artist was to indicate precisely whether the particular enemies of Christendom in the painting were Jews, Saracens or Roma.

In the 1427 entry of A Parisian Journal, the author notes:

‘But in spite of their poverty they had sorceresses among them who looked at people’s hands and told them what had happened to them or what would happen. [...] What was worse, it was said that when they talked to people they contrived [...] to make money flow out of other people’s purses into their own. I must say I went there three or four times to talk to them and could never see that I lost a penny...’20

Journal d’un bourgeois de Paris

The palm-reading scene in the foreground of the Haywain Triptych – presumably the work of a student of Bosch – is already remarked upon by Larry Silver in his monograph.21 In their 2001 publication, Bosch at the Museo del Prado, Carmen Garrido and Rogier van Schoute point out that a preliminary sketch was uncovered showing a Roma woman reading the palm of a foolish woman, while a thin child searched for her purse.22 Cuttler argues that this part of Bosch’s painting was not inspired by other images or life, but by a religious model: the palm reading in question is based on the visitation scene.

Another well-known representation of pickpocketing is a drawing displayed at the Louvre, which is also attributed to Bosch. It represents a conjurer and his audience, a motif he would return to for his later painting The Juggler. His wife, on the right, wears the typical Roma turban. On the left, in the audience, a figure points to the conjurer while putting his hand inside the pocket of the woman next to him.

Palm reading also appears in the tapestry housed at Gaasbeek Castle23 along with everyday scenes of music, dancing, childminding, etc. – representations based on actual observations of Roma and their lifestyle. Later on, from the sixteenth right up to the eighteenth century, the palm-reading scene gained widespread currency in Netherlandish and Flemish landscapes, sometimes combined with other elements such as the foolish lover or the prodigal son. These paintings were not only warnings for market-goers to be wary of pickpockets, but also criticised those who believed in fortune-telling. In 1427, for instance, the bishop of Paris condemned not the Roma but rather their superstitious clients.

Eager for details that were as lifelike as possible, the German masters of the fifteenth century took an interest in the clothes and lifestyle of Roma in the hope firstly of achieving historical accuracy in their representation of Egyptians, and secondly of finding oriental and exotic motifs. I think we should be sceptical about Cuttler’s conclusion that ‘Roma pretended to be refugees who were forced to escape religious persecution, but their lifestyle made them less and less welcome in cities’.24

Historical documents and visual products help us to reconstruct the migration routes of Roma, and it seems that in the early years they found refuge in many cities. Later, however, when they returned to places they had previously visited and the locals found their presence too permanent, and even threatening (in economic and political terms), they were made less welcome.25 It was around this time that they started to be demonised and criminalised, cast in barbaric, evil, ugly and thieving roles and featured in images thereof. While it is now certain that these images were not made to establish prejudices against Roma, these early representations, coeval with the appearance of the Roma in Europe, nevertheless still exert an influence that is stronger than the nineteenth-century romantic idealisations of Roma life.

Roma and other racialised minorities were the other side of Reason.

From the sixteenth until the eighteenth century, there are few works depicting real Roma individuals; the vast majority of images of Roma are purely fictive and act as representations of the antithesis of the Christian world. Somewhere in between the individual portrait and the personification of the foreigner/stranger are Roma who are depicted in grand-manner portraitures: acting as extravagantly dressed contrasts to their owners, their servitude sometimes emphasised by a silver slave collar or a silver ring in one ear. A similar category is that of Roma figures appearing as musicians and performers in pageants and ceremonies. Most of these representations of Roma are already claimed as images of black people, even though there are examples where the physiognomic details make Roma identification possible (because research has revealed that the images of black people feature exaggerated, well-calculated and recognisable distortion which makes them recognisably different from Roma depictions).

The scholar Barbara Johnson memorably defined a stereotype as ‘an already read text’.26 By the eighteenth century, many of the significations attached to Roma were already pervasive, imagined attributes and associations: diabolic darkness, magic, witchcraft, ancient wisdom, primitive innocence, savage ignobility or nobility, irrationality and an insatiable animal-like sexuality. Roma and other racialised minorities were the other side of Reason. Roma were on the one hand noble savages, embodying the innocence that mankind lost in its pursuit of material gains, while on the other hand serving as Europe’s ultimate ideal of ignobility.

The Enlightenment period, with its investment in the idea of civilisation, was a necessary precondition for the formation of primitivism. The idea of the ‘primitive’ is in binary opposition to the ‘civilised’: The word primitive cannot stand without its composite, ‘civilisation’, and the two terms actually constitute each other.

When we examine the Image of the Roma we find that Central Europe – and more specifically Hungary – receives a greater emphasis in our research, as the ‘Gypsy’ in eighteenth-century Hungary became the romantic alterity of the national character. Roma became the parable of national belonging even during the most challenging times. The invention of the print industry of the period and illustrated magazines were all part of the mass educational instruments sharing knowledge about the Hungarian people and their homeland. The various publishers tried competing with each other by producing diverse and interesting visual illustrations and, as a result, incentivised a rich vein of research into Hungarian people’s lives. Their role in the formation of the discipline of ethnography is quite significant.27 In these illustrations, we find a number of detailed drawings and genre woodcuts of traditional Roma costumes and occupations.

Music is a main component of the relationship between Hungarians and Roma. The album by Johann Martin Stock (1742–1800) had already devoted attention to ‘Gypsy musicians’, who later became permanent personae in the folkloristic publications presenting Hungarian ethnicities.28 Hungarian art historian Emese Révész has written a thorough and brilliant essay on how the figure of the ‘Gypsy musician’ gradually merged with depictions of Hungarians in European art and visual production, and how the characteristics of ‘Gypsy musicians’ were slowly incorporated into the Hungarian national self-image.29 Among other things, the essay also suggests that the common origin of Roma and Hungarians became a widely accepted notion in Europe. No matter how scandalous Ferenc Liszt’s statement about Hungarian music originating from Roma, i.e. ‘Gypsy musicians’ actually sounded, it was just an iteration of a widely known European topos.30

Subtitles and captions explain the kinship between the Hungarians and the ‘Gypsies’, as well as their similarity in character and psychology. Gábor Prónay noted that ‘He is the one who can perform the Hungarian song with the fire and soul fit for this nation’, as if ‘Gypsy musicians’ ‘had the talent to read the feelings of Hungarians to interpret them credibly’.31 A Sunday newspaper by the name of Vasárnapi Ujság [Sunday Night] called ‘Gypsies’ the only soul mates of Hungarians, ‘full of fantasy, cleverness, and originality. No matter if it’s a sad or happy day, the Hungarian can live without wine, but not without a “Gypsy”’.32 In several depictions of the pub scene, the Hungarian betyár is accompanied by his one and only fellow, the ‘Gypsy musician’. As an extension to this tendency, in the newspaper Ország Tükre [The Nation’s Mirror], Pál Jámbor compared the country’s Hortobágy region to ‘a Land of Promise, which bears simultaneously the rich natural resources of Egypt and the peace of Arcadia’.33

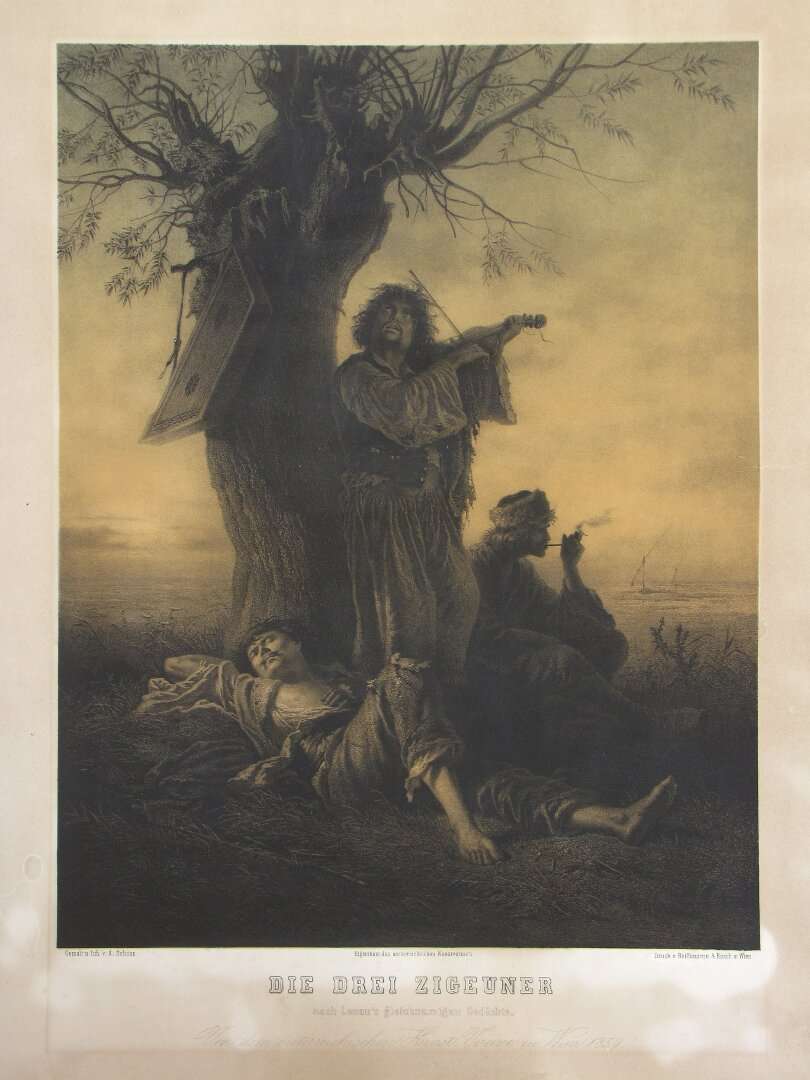

The illustration to Nikolaus Lenau’s poem ‘Three Gypsies’ is a further depiction of this notion.34 The image was accompanied by the Hungarian translation of the poem, which suggests that the balm for life’s troubles is a violin, pipe and dreams.

The lifestyle of ‘Gypsies’ becomes the emblem of what it is to be ‘bohemian’, living for momentary pleasures and art.

Thus, the lifestyle of ‘Gypsies’ becomes the emblem of what it is to be ‘bohemian’, living for momentary pleasures and art. Bohemia – a way of life embraced by artists and others in the early nineteenth century – was a counterculture. The originally French word, bohémien is actually a derogatory term for French Roma. Mike Sell in his essay ‘Avant-Garde/Roma: A Critical Reader in Bohemianism and Cultural Politics’35 argues that not only did Roma become a demographic presence in the bohemian world, but their very name became its index of authenticity and rebelliousness. As he explains elsewhere:

'[F]rom the very start bohemianism required an ideological supplement, a symbolic and performative fortification to resolve the contradiction between a sense of belonging and a sense of being hopelessly excluded. The ethnic group known as the Gipsy provided to those early bohemians – and to those who have forgotten them – both a conceptual structure and an ontological model for living virtuously and authentically apart from the mainstream.’36

Mike Sell

Art historian Marilyn R. Brown, in her book Gypsies and Other Bohemians: The Myth of the Artist in Nineteenth-Century France,37 considers the picturesque characteristic of this alternative political discourse and identity as a ‘response to and a sublimation of’38 the failure of the revolutions of 1830 and 1848.

Mike Sell uses Gustave Bourgain’s 1890 illustration Gypsies – which depicts a group of Barbizon artists sketching a group of Roma – to draw attention to the entanglement between artists and Roma in the work and, more broadly, to the bond and alliance between those who were somehow separate from society: whether as an elite, a subaltern, a visionary community or a ‘minority with a mission’.39 Sell thereby demonstrates the Roma presence in Bohemia and the bohemian presence in the history of the avant-garde (and the history of art) while also reminding his readers of the erasure of Roma from the stories we know.

Sociology professor Éva Judit Kovács, in her groundbreaking and comprehensive essay ‘Fekete testek, fehér testek’ [Black Bodies, White Bodies] examines how Roma were depicted by the painters of Hungarian modernity.40 Kovács co-curated the exhibition organised at the Krems Kunsthalle in Austria which presented the Roma image of modernity.41 The conclusion of her extensive research is that

‘Central European societies create their own ‘blackness’ through ‘savages’ and through their faraway and nearby colonies. In the panoptic regime of Central European modernity Roma become pendants of the African and Asian “primitives” of Western Europe.’

The essay serves up plenty of examples of both Romaphobia and Romaphilia, while using several case studies to demonstrate how the Roma body is denigrated, sexualised and feminised in modernity. It also draws attention to the white majority’s attitude, desire and mood, which she claims is ‘projected onto the Roma body’.

A good example of the differing attitudes of the period is available in the oeuvre of – and actually in one specific composition by – Lajos Kunffy, who was declared ‘le peintre de Zigan’ by the newspaper Paris-Midi in 1913 after his exhibition in Paris. His diary contains detailed descriptions about Roma in his paintings:

‘I started painting Gypsy pictures in 1905. I found these people very picturesque, as they were making wooden troughs sitting around their canvas tents, cooking; their children were running around naked, making a primordial, primitive impression. There is no doubt they are from India.

When Albert Besnard returned back home to France from his Indian tour, and I saw the types he collected, I even told him that he needn’t travel that far, he can find figures like this in Hungary. [...]

My Gypsy pictures sold well, I hardly have any left. [...] But what happened to these Gypsies? They stopped wearing long hair. In 1914 those who were conscripted to the army had their hair cut short. [...] They came back to me after the war, so that I would paint them, because they liked this easy income, but with short hair. Later on, even the children cut their hair, because they figured it was more comfortable that way.

I was less interested in the men this way; I just painted a few pretty girls, or the so called Kolompár Gypsies, whose costumes are a lot more colourful.’42

Lajos Kunffys: Two Gypsies

The notion of the ‘Gypsy’ figure as black is present in literary sources and contemporary discourses alike. As Ian Hancock notes, ‘Roma have long depended on a system of black/white imagery’. He describes how the Romani word for Eastern Europe (i.e. Romania and Bulgaria, where the highest number of Roma live) is Kali Oropa or ‘Black Europe’.43

Given that the first Roma artists were ‘discovered’ in the naïve art movement, it is important to contextualise this phenomenon briefly. The first mentioning of naïve painters originates from the end of the eighteenth century. The revolution brought both social and societal change; in the words of the writer and revolutionary Louis Antoine de Saint-Just, ‘Europe has a new concept about happiness’, in which everybody has the right to explore their identity.

The three key artists of French naïve painting – Cheval, Abbé Fouré and Henri Rousseau – were born at the height of bitterness in the mid-nineteenth century. A lack of written sources means that we know very little about their early activities. It was not until 1885–86 that Rousseau grabbed the attention of the public. The main source of this renewal was the exoticism of extra-European cultures and the primitive art promoted by the world’s fairs. Paul Gauguin, viewed European Art as becoming increasingly ’empty’, felt the call of ‘the new paradise on Earth’ in Tahiti as a new and plenteous source of inspiration for modern art.

There were also new developments in the field of literature which sought to ease the burden of everyday challenges. These can be viewed as analogous to the developments in visual arts. In 1785, a collection of popular stories and fairy tales from all corners of the world including the One Thousand and One Nights (also known in English as the Arabian Nights) was published in Paris and Amsterdam. These were translated from Arabic to French by Antoine Galland, the French ambassador to Constantinople. An even more important development is the work Voyages Imaginaire, Romanesque, Merveilleux, published between 1787 and 1789. This is one of the pioneers of science-fiction literature, which appeared at around at the same time as the Grimm brothers began collecting fairy tales. These literary creations proved fertile ground for similar progress in visual art.

The modern history of naïve art starts with Henri Rousseau’s introductory exhibition at the Salon des Indépendants. Its success triggered an interest in naïve art round Europe, from Paris to Munich and all the way to Moscow. The notion of ‘naïve art’ is first used in a Hungarian context in Jenő Bálint’s essay about the popular peasant painter Péter Benedek:

‘That saintly naivety radiating from what he paints or says is an asset to his personality, and testifies to the most respectable qualities of a primordial artist. His naivety comes from the bottom of his soul; it is childlike and unconscious.’44

From 1934, Bálint rented a permanent exhibition space in Budapest at Erzsébet Square 2, where he could present naïve artworks to the public. He subsequently organised an exhibition in the city in 1938, and then in Vienna at the Kunstlerhaus in 1939. Based on these successes, he continued his search for naïve talents.

The public and the critics received the new initiative well,45 and Bálint’s naïve painters – who later formed an association – became popular throughout Hungary. The association published its own periodical, Hungarian Talent, revealing its achievements to the international scene. In 1934, for instance, the Swedish newspaper Dagladen published a long article full of praise about their activities. In 1937, the Dutch Avondblad paper wrote that ‘their art demonstrates Hungarian originality in a captivating manner’.46 In 1938, they exhibited in the Netherlands under the title Hongaarse Oertalenten, and art historian Vernon Duckworth interviewed them for London radio.

Soon after the success of Péter Benedek, the Hungarian Népművelési Intézet [People’s Education Institute] and the Hungarian National Gallery began systematic research into art by non-professionals. In 1971, the Hungarian National Gallery organised an exhibition for naïve art that featured the Rom János Balázs. A total of 152 artists applied to the open call published by ethnographers Ida Mihály and Pál Bánszky, and the final exhibition presented fifty artists and 106 of their artworks. The catalogue reads: ‘Naïve art is both a social and artistic phenomenon, claiming a space in the history of our art.’47

Although several Roma painters were popularised by the naïve wave and the publications and research of Pál Bánszky, some of the most fundamental characteristics of Roma art remained unexamined in this context: trends of abstraction and conceptual intentions, the gender-specific themes revealing the double minority position of women, the hyperrealism of the young generation, or the social critique and politics so actively present in the works of Roma artists.

Very few of the many thousands of representations of Roma throughout the ages are of ‘real people’.

What do these artworks and images of Roma reveal about the object they depict, namely the Roma people? In representations of the nineteenth and even twentieth centuries, physiognomic authenticity is still not the priority of artists. As the Roma object on the picture becomes the ‘artwork’ – which takes on specific semantic structures – it is no longer about ‘something, but embodies something, that is about something.’48 Retrospective research is not yet available on the stories of the depicted, i.e. the Roma models, and their role in shaping the empire of Western art.

One potential realisation of the desired decoloniality is by reconstructing the stories belonging to Roma ‘models’ of the past. Very few of the many thousands of representations of Roma throughout the ages are of ‘real people’. Until the end of the eighteenth century, the genre of portraiture in painting and sculpture was concomitant with a certain prestige and social status. There are hardly any examples of realistic portraitures presenting Roma in the social elite: in 1827, popular violinist Pista Dankó was portrayed, and in 1820, János Donát painted a portrait of János Bihari, who served as musician to the Archduke of Austria. The only Roma woman whose realistic portrait was commissioned in nineteenth-century Hungary was Aranka Hegyi, actor, opera singer and national celebrity. Adolf Fölsch painted her in 1887, and distinguished sculptor Alajos Stróbl created his Dancer after her.

The ‘Gypsy topic’ lived on as a curiosity both in Budapest and in Munich. Simon Hollósy, a former student at the Munich Academy, and his young followers formed the Nagybánya artists’ settlement to devote their careers to plein-air paintings. As Béni Ferenczy recalls:

'Only the Gypsies were willing to show themselves naked; miners’ daughters or village girls would pose for nudes only when they were on the downhill slope to debauchery, and even this did not last long, because their short model careers ended in the local brothel or the one in Szatmár.

But the majority of Gypsy girls were also only prepared to get partially naked, undressed to the waist, or not even that far. The most beautiful one, Eszter Krajcár, the card reader on my father’s three-part composition of Gypsies, would pose for anyone but only when clothed.’49

Béni Ferenczy

We should also remember the fertilising effect of the ‘perfect model’ in the art of József Rippl-Rónai. Upon meeting Fenella Lowell, the American-Roma woman who modelled for Rodin, Bourdelle and Hungarian artists in Paris, he invited her to Hungary, where she became a resident of his Villa Róma. She often posed naked for the artist, and the most famous nude photographer of the time, Olga Máté, also took photographs of her. Rippl used these photos for his famous nude series, in which the naked bodies linger in the garden of the Róma Villa in an Arcadian atmosphere. The most developed work in the series My Models in My Kaposvár Garden (1911) positions the artist as the mythological Paris, forced to choose from among the three goddesses.50

Conclusion

It was during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries that the imaginings which created the subaltern position of Roma in Europe first emerged, a position that the art and visual production of subsequent centuries went on to reproduce. Although the politics of representation changes with the major historical periods, its oppressive characteristics are constantly present throughout the history of art and merely vary between stronger and more blurred varieties.

It might seem that this essay takes a fundamentally anti-representational position. It considers a divergence of perspectives, such as the idea of alternative representations developed by social psychologist Allex Gillespie, whose research delves into psychoanalysis in order to examine how people engage with alternative representations of other groups. It provides an opportunity to understand the dialogical potential of alternative representations, which is quite simply necessary for enabling groups to talk about the views of others.

...re-claiming the ‘Gypsy models’ from the history of art as part of Roma history...

Any attempt to reconstruct the historical presence of Roma must engage and deconstruct the deeply embedded myths of authenticity surrounding both Roma and European cultural dissidence.51 It is not enough to merely understand the ‘relations of representations’ that Western art entails for Roma. As Walter Mignolo claims, Roma need to ‘de-link’ from what has been taught theoretically, politically and empirically, and to ‘un-learn’ the usual mechanisms in order to open up the possibility of innovating the ‘politics of representation’.52 This innovation is only achievable if Roma become aware of the background that they stand out of. Reconstructing the Roma contribution, in other words reinstituting the power of the Roma as avant-garde and re-claiming the ‘Gypsy models’ from the history of art as part of Roma history will shed new light on the operation of hegemonic powers in Western art and its history.

Of course, another obvious option for Roma is creating images of their own...

(I presented the fifteenth to eighteenth centuries in this essay in a Collegium Artium Workshop at the Institute for Art History, Hungarian Academy of Sciences in May 2012, where distinguished art historian colleagues contributed with ideas and criticism to this research.)