On the Ethics of Photography and Images in a Sinti and Roma context – The tale of the Rodriguez family, a personal journey to regain our self-image

Kale Thai Shukar (Too “Roma” for our Family Album)

I remember opening old family albums as a child and looking at my own relatives with unfamiliar eyes. They all looked extremely well-dressed, they were in restaurants and public squares, smiling and posing, detached from the extreme poverty and persecution we constantly faced. At first I thought that nobody wanted to look troubled and tortured in a family album, that everyone had selected their best-looking, happiest pictures. I soon realized that there was something else going on.

Growing up, I heard stories of extreme poverty and persecution. By extreme poverty I don't mean not having electricity or water, because that was something I myself did not always have. Extreme poverty a decade before I was born meant not having tried ham or yogurt until you were in your 30s and not to have a toilet until your 20s. Jokingly and ashamed, my uncle Luis told me once that he was 14 when he first saw a flush toilet and he literally did not know what he was supposed to do with it. Try to picture mentally, just for ten seconds, a community as isolated as Madagascar, which lived on its own for centuries and had little if any interaction with non-Roma people (except, of course, the constant persecution and pogroms). This level of structural poverty, resulting from centuries of racism, is extremely hard to explain or understand.

My mother in particular told me about living in a (literal) cliffhanger on top of some kind of small mountain, with no utilities of any kind, no access to any public services, no birth certificates or documentation, etc. Yet the few pictures she still keeps from that time show her dressed perfectly with a perfect, smiling family... interesting.

One day I had a revelation. I brought a non-Roma friend home to share some family stories, and I soon realized that the decorations of the whole house had been changed. My parents dressed up as though they were the King and Queen of England, and all the stories and physical evidence of poverty and struggle were expunged.

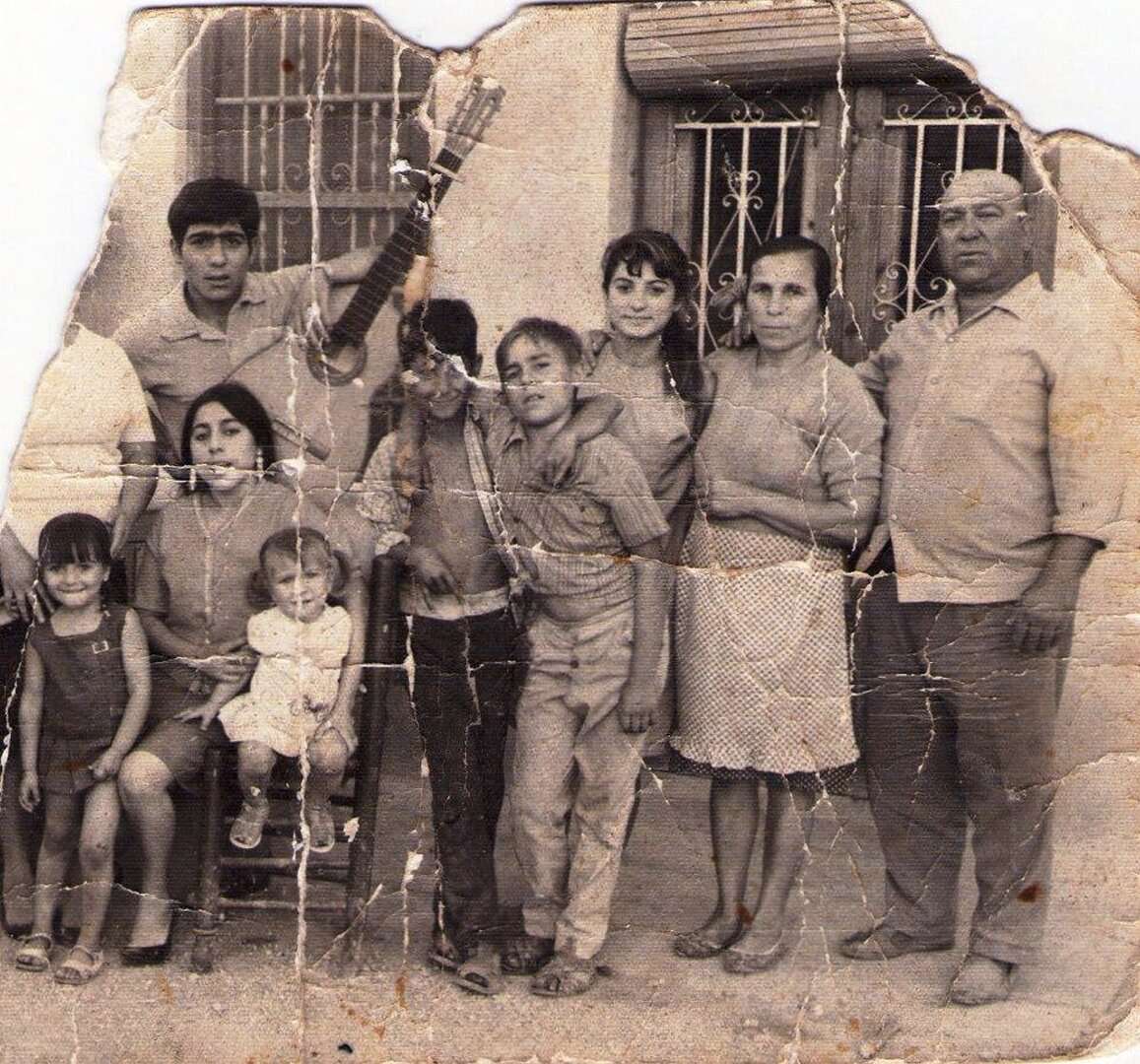

The same day, while showing some old albums to my friend, a picture fell down. It was a family picture in black and white, but somehow it had not made the “final cut” of our family story.

On the right of the photograph, my grandpa is dressed casually, wearing some old sandals; my grandma looks beautiful with her dotted apron; my father, the “blonder” boy, looks a mess and so does the cousin hugging him; in the corner my aunt Bienvenida shows her beautiful long black hair, wearing her golden-coral earrings (a typical item for Spanish Roma women); finally, in the upper left corner, my uncle Miguel with his guitar shows some darker features.

I understood clearly that this picture had been censored. Out of fear, my family constructed the image of a life they had never lived, a life to show in the rare moments they met or talked to non-Roma, and a life to show themselves to calm their own anxiety.

Asking my parents and relatives, I found many pictures like this, some older, some more recent, but all abandoned in some lost, dark drawer.

Why were my parents so afraid to reveal their real family pictures? I'll tell you right now, they were terrified to look the way others expect Roma to look.

Because even now Roma don't own their own image. Publications and newspapers keep bombarding us with images of poverty and dark-skinned people and associating these images with crime, failure and doom.

Looking through my own family pictures, I realized that it is not within the images that an ethics must be found; the real poison usually lies in the message that accompanies the pictures.

In fact, at this point in history, sometimes it makes no difference if the picture has no message, since the narratives are now part of European folklore and popular culture. For example, if a blonde non-Roma child appears barefoot in a family picture, society will read it as a child playing. If the child is Roma, the assumption is that they are neglected by their parents. The same applies to most imagery associated with Roma, while non-Roma are immune to this specific gaze. Roma are instantly charged with the worst crimes of humanity if they dare to allow anybody to share a picture that portrays them in any way... so what to do?

An ethical approach to the subject of photography and images in the Sinti and Roma context will probably rely on the value of self-representation and Roma historical revisionism, that is, a re-interpretation of the historical record. This entails challenging the orthodox views held by non-Roma professionals of all disciplines.

I have managed to collect hundreds of non-edited family pictures of The Rodriguez family. I have chosen to take pride in our history and circumstances, including both the good and the bad, and I keep loving my family, reminding them that there is nothing to be ashamed of in the way they have been living and surviving their whole lives. On the contrary, as African Americans once said, Black and Beautiful, Kale Thai Shukar!

Rights held by: Vicente Rodriguez Fernández| Licensed by: Vicente Rodriguez Fernández| Licensed under: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International | Provided by: RomArchive