Website of Roma Rising: www.romarising.com

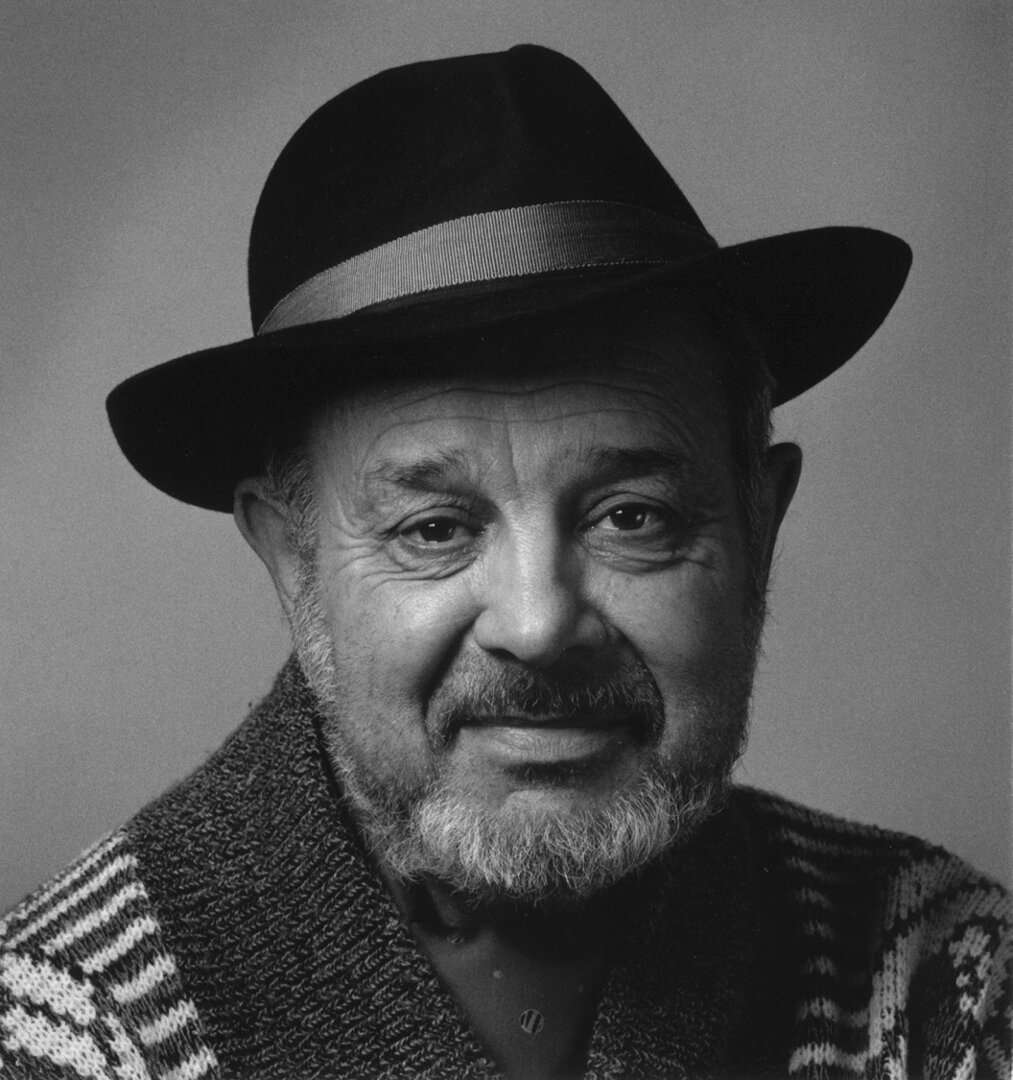

Chad Evans Wyatt | Karel Holomek | photography | Czech Republic | 1990 - 2017 | pho_00060 Rights held by: Chad Evans Wyatt | Licensed by: Chad Evans Wyatt | Licensed under: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International | Provided by: Chad Evans Wyatt – Private Archive | More at: RomaRising

Website of Roma Rising: www.romarising.com

In 2000, I set about to photograph a maligned minority in the Czech Republic after reading appalling harangues in the press. Roma were described as having genetic deficiencies, corrupted social behaviours, and an inherent inability to conform to majority expectations. I did this as a minority myself, I saw in the persecution of Roma the same pressures from a social majority that bedeviled African Americans. I did this also as tribute to the Civil Rights Era in the U.S., in which my parents had participated. I did this in response to the clarion call of Dr Martin Luther King, Jr, “I look to a day when people will not be judged by the colour of their skin, but by the content of their character.” Doctors, bankers, businessmen and women, all manner of professionals had come to our flat in New York when I was very young. I became determined to find and portray Roma citizens who earned degrees, lived “normal” lives, and paid their taxes.

A fundamental problem from the start was to find an untried photo language. My intention was to present people thought not to exist in an original light. Even though the portraits are not the usual “Gipsy” pictures, few, save cultural anthropologists, have expressed interest in this aspect of RomaRising. I needed a coherent style, and found it. The dedicated Roma press have shown remarkable understanding of the principles that motivated me. The general media often miss the point. RomaRising images corrode stereotype.

Back to the beginning. I formed a style by making æsthetic decisions, and examining the past efforts of others at portraying minorities. Some of those portrayals were successful, others allowed cultural prejudice to colour result. Further, I needed a title for the project. The Roma middle class and professional class of the Czech lands had been decimated by the Nazi killing machine. I had my metaphor. “RomaRising” appealed to me, because, by some miracle, there was a phoenix of a new middle class of Roma a half-century later.

My friend and former Director of the Film School FAMU in Prague, Prof Miroslav Vojtěchovsky, describes common portrayals of Roma as Theatre of the Grotesque. Sadly, even today, the media publish garish and despairing images, which lock Roma into a frustrating box of rôle-playing for the camera. This occurs even in photographs commissioned by governments and NGOs.

Edward S. Curtis, the celebrated US portrayer of Native Americans during the early 20th century, also encouraged role-playing for the camera. Often, individuals posed for Curtis, then removed their costume, and drove home in their Model T Fords. This amounted to a performance, since those portrayed were emulating the practices of their ancestors. Finding the genuine in the monumental body of Curtis’ work is difficult, at best.

Prior to Curtis, and unlike him, Guido Boggiani photographed the Chamacoco tribe of Paraguay, as they were. The striking authenticity of these images is obvious. There is no posing, although there is certainly communication between photographer and subject. My interest then turned to August Sander, who also pursued transparent conversation between subject and viewer. Yet another photographer, the great Josef Koudelka, produced seminal images of Roma in the mid-twentieth century. His images underscore the importance of honest images in current time. Koudelka also invokes the transparency of Sander. Boggiani, Sander, and Koudelka. There is one more. Finally, RomaRising images are for the most part “Environmental Portraits,” in the manner of Arnold Newman, where subjects are photographed in their own surroundings.

Unfortunately, Koudelka's sacrifice and dedication were not emulated by those who simply copied his work imperfectly. With some notable exceptions, generations of very bad photography followed his breakthrough images of Roma. Although unable to devote continuous months to living among Roma as Koudelka had done, I did spend more than a year in producing my portraits.

And, I had something of my own to bring to the table. In my commercial work, I am a portraitist. The use of studio lighting, plus black and white media give a respectful and unemotional view of Roma who are accomplished in terms society can respect. The pressure non-Roma might feel when observing these portraits is thereby greatly eased. This is an opportunity to look deeply, for what might be the first time, into the visage of a fellow-citizen who happens to be Roma. My photos challenge only stereotype. They are quiet and respectful, inviting contemplation. This approach was instantly successful, even when exhibitors added dancers and folklore to exhibitions of the images (thus demonstrating little understanding of the project’s intent).

The RomaRising series has distinction and historic value, even in the sea of other photographic voices. The Roma and Sinti I have portrayed echo Koudelka's own comment to me, “Finally, someone has done this.” Meaning, that finally here was an authenticity of cultural content, and not just an emulation. My goal is to shatter stereotype.

A word about gender. RomaRising has, from the very first, enjoyed the support and participation of women of great capability and adroitness. Indeed, a subtheme of the project is the growing empowerment of Roma women. These gifted women inhabit all the folios. They have my unqualified gratitude, and without them, there would be no RomaRising.

A word about the practical: the original folio, RomaRising Czech Republic, was silver-based on 6x6cm film, and printed in a wet darkroom. The remaining folios, Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Canada, Bulgaria, and Romania were photographed digitally. Today, printing is done from digital files, on a variety of media. My first idea, to realise images on 4x5” (9x12cm) sheet film, was abandoned after the attacks on September 11 of 2001. I had wanted to make images so large (5 feet tall, or 1.5 metres) that they were psychologically undeniable. Suddenly, tightened airport security meant that sheet film in boxes would not survive more stringent x-ray and examination by hand. Hence, a return to 6x6cm roll film.

I found my first subjects in the Czech Republic by asking well-respected scholars, photographer friends, and Roma friends from the first project I did Europe, 101 Artists in the Czech Republic (2000). The reputation of the project grew rapidly. People came to expect my call. RomaRising enjoys Europe-wide recognition today. The project has little trouble finding and asking people to participate.

From the beginning, one element was absent. There were no true biographical commentaries about the subjects. Funds were not available for more than basic questionnaires. I am honoured that Mary Evelyn Porter has contributed deep and comprehensive interviews and narratives to the latest RR folios, Bulgaria and Romania. Subjects are given voice to describe the avenues to their successes. Individuals come alive. Ms Porter’s work has been universally admired. Her contribution is very much the counterpart to my own effor to make visible those not thought to exist, to understand the invisible.

One nearly crippling fact had to be overcome. The work is self-funded, with the exception of the RomaRisingPL folio, and a small stipend from ArtsLink in New York. Had there been underwriting, RomaRising might have visited twice the number of countries. Instead, the project’s viability was limited by the need to borrow funds from my own photography business. Appeals to NGO and EU entities produced a universal response: I was not European, I was not living in Europe, I was not Roma. Meanwhile, bureaucrats across the continent funded forgettable public relations images. In 2007, after one particularly disappointing rejection, I decided to abandon the project. Then, a small NGO in Poland, PROM, asked that I produce a RomaRisingPL. I agreed. The project continued.

I was driven to achieve portraits of Roma and Sinti in seven countries by my own background. My parents were involved in the stirrings of the early Civil Rights Era in the U.S. In the experience of Roma and Sinti of Europe, I saw a chance to contribute to the historic quest for human rights and emancipation. Among the 400 portraits of RomaRising, one can find taxi drivers, lawyers, accountants, designers, doctors, writers, even a flower vendor (www.romarising.com). I am honoured that my hopes were taken to heart, and that so many came to my camera – some at personal risk – to make RomaRising the sole independent statement on Roma and Sinti during the first twenty years of the Twenty-First Century.

Washington, DC, July 2017

Rights held by: Chad Evans Wyatt | Licensed by: Chad Evans Wyatt | Licensed under: CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International | Provided by: RomArchive