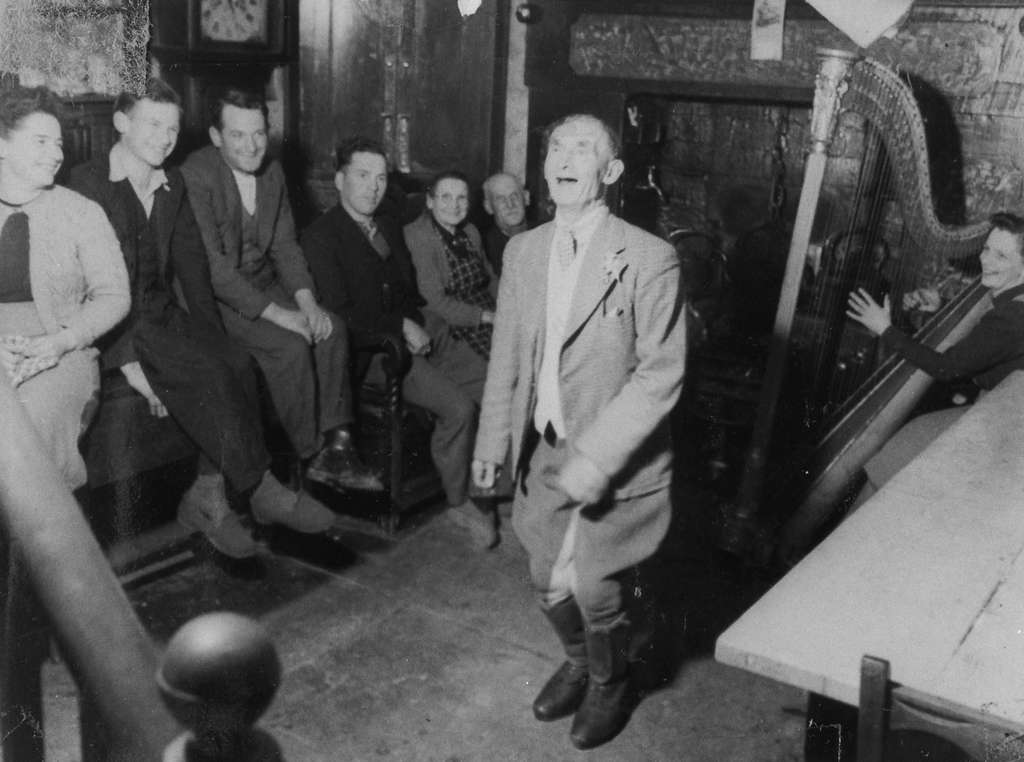

‘I first met Riley Smith at a talent competition for Gypsies, Roma and Travellers. It was almost all singers, a few musicians, and then there was Riley. Nobody could believe how well he kept time, and how fast he could dance. Fewer Romany Traveller people are doing the traditional step-dancing and tap-dancing these days. Suddenly there was a teenager in front of us who wasn’t just a throwback – he looked like he was probably even better at dancing than his forebears had been.

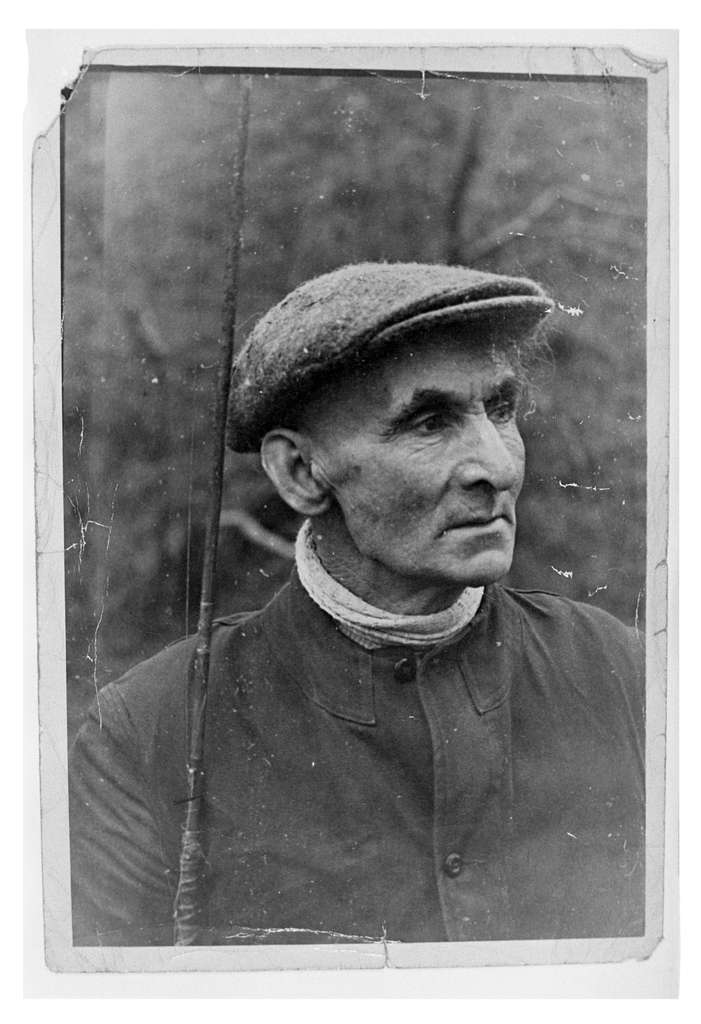

Riley was with his Dad. I could see how proud Riley’s Dad was of him, and of his dancing. That was what really interested me about it. English Romany men have a reputation for being tough, as many undoubtedly are. Riley’s dad looked tough but he was also clearly delighted to watch his son tap-dance for a crowd. Watching him stand up to clap and cheer as Riley won the competition, it seemed like the tension between masculinity and the arts was just a mirage.

I called Riley up and rokkered (to speak) to him about the possibility of making a film. He said he was up for it and wanted to know if it would be like a film called Cherry Orchard that the Romany journalist Jake Bowers had made about Riley’s uncles when they went to pick cherries. I said yeah, it could be a bit like that, and reassured him that the quality would be good. As DoPs I would have two seasoned short film directors – Charles Newland, also a Romany Gypsy, and Phillip Osborne, an old friend of mine and my family’s who I trusted to understand the cultural sensitivities. So we had a great team who all knew the culture intimately.

I had an image in mind of Riley tap-dancing under a tree at sunset but we didn’t manage to get that shot – I explained the idea and I think he thought it was a bit weird. But I think the shots we did get were strong. I particularly like the one of Riley’s dad kissing his baby grandson while we can hear the tap dancing in the background. It’s just a side of Romany men that the public never gets to see. You could argue that the shots with the horses are stereotypical, but the Romany relationship to horses is very important to us and I thought it set the scene.

We made the film for a pittance: the price of our diesel whatever we might have lost by taking the time off to make it. Riley’s mum kept us fed all day with tea, cake and stacks of sandwiches.

I had another motivation for making the film. Through years of working as a journalist and sometime Romany rights activist, I had been in contact with Roma people from many different countries. On one level this was amazing: it broadened my horizons and helped me see how diverse our community was, and I made some great friends. But at another level it was depressing. People constantly questioned the cultural authenticity of British Romany people, largely based on our skin colour, our command of the Romani language, and the fact that musicality didn’t seem to play a central role in our culture. It was assumed that Eastern Europe – possibly alongside Spain – was the centre of Romany culture, and that our country was a backwater full of inauthentic ‘Gypsies’. There were cracks in this argument everywhere I looked – the Romungre Roma of Hungary do not speak Romani, and there were fair-skinned and blue-eyed Roma in every community I encountered ... But the assumption was still there.

With Riley and his family, I saw the opportunity to rebut some people’s assumptions about our community. Contrary to some of the refrains I often hear, many of us are dark-skinned and – due to this as well as our accent and the Romani dialect we speak – visibly identifiable as Gypsies to the surrounding community. And for some of us, music and dance are part of an ancient way of life. In these respects, I think the film speaks for itself.

And really, as its DoP/editor Phillip Osborne put it, “It’s really just a film about a father’s pride in his son”. We showed Riley’s dad some of the rushes after we’d shot them on the day. His face lit up, and he said “Cor, ain’t that clear?”.’

Damian Le Bas, London, 20 September 2017